In the first half of the twentieth century, the Soviet Union and the Communist parties of the Third International around the world mainly came to represent socialism in terms of the Soviet model of economic development, the creation of centrally planned economies directed by a state that owns all the means of production, although other trends condemned what they saw as the lack of democracy. In the UK Herbert Morrison said "Socialism is what the Labour government does", whereas Aneurin Bevan argued that socialism requires that the "main streams of economic activity are brought under public direction", with an economic plan and workers' democracy.[2] Some argued that capitalism had been abolished.[3] Socialist governments established the 'mixed economy' with partial nationalisations and social welfare.

By 1968, the prolonged Vietnam War (1959–1975), gave rise to the New Left, socialists who tended to be critical of the Soviet Union and social democracy. Anarcho-syndicalists and some elements of the New Left and others favored decentralized collective ownership in the form of cooperatives or workers' councils. At the turn of the 21st century, in Latin America, Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez championed what he termed 'Socialism of the 21st Century', which included a policy of nationalisation of national assets such as oil, anti-imperialism, and termed himself a Trotskyist supporting 'permanent revolution'.[4]

Contents

- 1 Origins of socialism

- 2 Marxism and the socialist movement

- 3 International Workingmen's Association (First International)

- 4 Paris Commune

- 5 The Second International

- 6 Anarchism

- 7 Social democracy to 1917

- 8 The inter-war era and World War II

- 9 The Post-war era (1945-85)

- 10 The Soviet Union and Eastern Europe (1945–1985)

- 11 Final years for the Soviet Union 1985-91

- 12 China (1945–65)

- 13 Socialism in China since the Cultural Revolution

- 14 21st century democratic socialism in Latin America

- 15 The emergence of a "New Left" in the developed world

- 16 See also

- 17 Notes and references

- 18 Further reading

- 19 External links

Origins of socialism

Some of the verses of the Bible which inspired the communal arrangements of the Anabaptist Hutterites are Acts 2, verses 44 and 45:"All the believers were together and had everything in common. Selling their possessions and goods, they gave to anyone as he had need."Acts 4, verse 32:

"All the believers were one in heart and mind. No one claimed that any of his possessions were his own, but they shared everything they had."and Acts 4, verses 34 and 35:

"There were no needy persons among them. For from time to time those who owned lands or houses sold them, brought the money from their sales and put it at the apostles' feet, and it was distributed to anyone as he had need."In Britain Thomas Paine proposed a detailed plan to tax property owners to pay for the needs of the poor in Agrarian Justice [5] while Charles Hall wrote The Effects of Civilization on the People in European States denouncing capitalism effects on the poor of his time[6]

Chartism "formed the first organized labour movement in Europe, gathering significant numbers around the People’s Charter of 1838, which demanded the extension of suffrage to all male adults. Prominent leaders in the movement also called for a more equitable distribution of income and better living conditions for the working classes. The very first trade unions and consumers’ cooperative societies also emerged in the hinterland of the Chartist movement, as a way of bolstering the fight for these demands."[7]

By 1842 socialism "had become the topic of a major academic analysis by a German scholar, Lorenz von Stein, in his Socialism and Social Movement.[8] According to an 1888 volume of A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles, the word socialism was coined on 13 February 1832 in Le Globe, a liberal French newspaper of Pierre Leroux.[9] The term "socialism" was further described in 1834 by Leroux[10] and Marie Roch Louis Reybaud in France. In England Robert Owen was also using the term independently around the same time. Owen is considered the father of the cooperative movement.[11]

The first modern socialists were early 19th century Western European social critics. In this period socialism emerged from a diverse array of doctrines and social experiments associated primarily with British and French thinkers—especially Robert Owen, Charles Fourier, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Louis Blanc, and Saint-Simon. "Associationism" was a term used by early-19th-century followers of the utopian theories of such thinkers as Robert Owen, Claude Henri de Saint-Simon and Charles Fourier to describe their beliefs.[12] These social critics criticized the excesses of poverty and inequality of the Industrial Revolution, and advocated reforms such as the egalitarian distribution of wealth and the transformation of society into small communities in which private property was to be abolished. Outlining principles for the reorganization of society along collectivist lines, Saint-Simon and Owen sought to build socialism on the foundations of planned, utopian communities. According to Sheldon Richman, "[i]n the 19th and early 20th centuries, 'socialism' did not exclusively mean collective or government ownership of the means or production but was an umbrella term for anyone who believed labor was cheated out of its natural product under historical capitalism."[13]

According to some accounts, the use of the words "socialism" or "communism" was related to the perceived attitude toward religion in a given culture. In Europe, "communism" was considered to be the more atheistic of the two. In England, however, that sounded too close to communion with Catholic overtones; hence atheists preferred to call themselves socialists.[14]

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, Comte de Saint-Simon, founder of French Socialism

Josiah Warren is widely regarded as the first American anarchist,[16] and the four-page weekly paper he edited during 1833, The Peaceful Revolutionist, was the first anarchist periodical published,.[17] Anarchist Peter Sabatini reports that in the United States "of early to mid-19th century, there appeared an array of communal and "utopian" counterculture groups (including the so-called free love movement). William Godwin's anarchism exerted an ideological influence on some of this, but more so the socialism of Robert Owen and Charles Fourier. After success of his British venture, Owen himself established a cooperative community within the United States at New Harmony, Indiana during 1825. One member of this commune was Josiah Warren (1798–1874), considered to be the first individualist anarchist".[18] For American anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster "It is apparent ... that Proudhonian Anarchism was to be found in the United States at least as early as 1848 and that it was not conscious of its affinity to the Individualist Anarchism of Josiah Warren and Stephen Pearl Andrews ... William B. Greene presented this Proudhonian Mutualism in its purest and most systematic form.".[19] There were also currents inspired by dissident Christianity of christian socialism "often in Britain and then usually coming out of left liberal politics and a romantic anti-industrialism"[8] which produced theorists such as Edward Bellamy, Frederick Denison Maurice and Charles Kingsley.[20]

Henri de Saint-Simon

Henri de Saint-Simon (born Oct. 17, 1760, Paris, Fr.—died May 19, 1825, Paris), and Karly Roesling, who is called the founder of French socialism, argued that a brotherhood of man must accompany the scientific organization of industry and society. He proposed that production and distribution be carried out by the state, and that allowing everyone to have equal opportunity to develop their talents would lead to social harmony, and the traditional state could be virtually eliminated, or transformed. "Rule over men would be replaced by the administration of things."[21]Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier (7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French utopian socialist and philosopher. Fourier is credited by modern scholars with having originated the word féminisme in 1837;[22] as early as 1808, he had argued, in the Theory of the Four Movements, that the extension of the liberty of women was the general principle of all social progress, though he disdained any attachment to a discourse of 'equal rights'. Fourier inspired the founding of the communist community called La Reunion near present-day Dallas, Texas as well as several other communities within the United States of America, such as the North American Phalanx in New Jersey and Community Place and five others in New York State. Fourierism manifested itself "in the middle of the 19th century (where) literally hundreds of communes (phalansteries) were founded on fourierist principles in France, N. America, Mexico, S. America, Algeria, Yugoslavia, etc."[23]Robert Owen

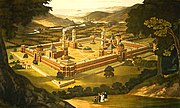

New Harmony, a utopian attempt; depicted as proposed by Robert Owen

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism in the United States |

|---|

|

The UK government's Factory Act of 1833 attempted to reduce the hours adults and children worked in the textile industry. A fifteen-hour working day was to start at 5.30 a.m. and cease at 8.30 p.m. Children of nine to thirteen years could be worked no more than 9 hours, and those of a younger age were prohibited. There were, however, only four factory inspectors, and this law was broken by the factory owners.[25] In the same year Owen stated:

| “ | Eight hours' daily labor is enough for any [adult] human being, and under proper arrangements sufficient to afford an ample supply of food, raiment and shelter, or the necessaries and comforts of life, and for the remainder of his time, every person is entitled to education, recreation and sleep.[26] | ” |

Owen's son, Robert Dale Owen, would say of the failed socialism experiment that the people at New Harmony were "a heterogeneous collection of radicals, enthusiastic devotees to principle, honest latitudinarians, and lazy theorists, with a sprinkling of unprincipled sharpers thrown in."[27] The larger community lasted only until 1827 at which time smaller communities were formed, which led to further subdivision, until individualism replaced socialism in 1828. New Harmony was dissolved in 1829 due to constant quarrels as parcels of land and property were sold and returned to private use.[27]

Individualist anarchist Josiah Warren, who was one of the original participants in the New Harmony Society, asserted that the community was doomed to failure due to a lack of individual sovereignty and private property. He wrote of the community: "It seemed that the difference of opinion, tastes and purposes increased just in proportion to the demand for conformity. Two years were worn out in this way; at the end of which, I believe that not more than three persons had the least hope of success. Most of the experimenters left in despair of all reforms, and conservatism felt itself confirmed. We had tried every conceivable form of organization and government. We had a world in miniature. --we had enacted the French revolution over again with despairing hearts instead of corpses as a result. ...It appeared that it was nature's own inherent law of diversity that had conquered us ...our 'united interests' were directly at war with the individualities of persons and circumstances and the instinct of self-preservation... and it was evident that just in proportion to the contact of persons or interests, so are concessions and compromises indispensable." (Periodical Letter II 1856).

In a Paper Dedicated to the Governments of Great Britain, Austria, Russia, France, Prussia and the United States of America written in 1841, Owen wrote: "The lowest stage of humanity is experienced when the individual must labor for a small pittance of wages from others."[28]

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon pronounced that "Property is theft" and that socialism was "every aspiration towards the amelioration of society". Proudhon termed himself an anarchist and proposed that free association of individuals should replace the coercive state.[29][30] Proudhon, Benjamin Tucker, and others developed these ideas in a mutualist direction, while Mikhail Bakunin, Piotr Kropotkin, and others adapted Proudhon's ideas in a more conventionally socialist direction.In a letter to Marx in 1846, Proudhon wrote:

| “ | I myself put the problem in this way: to bring about the return to society, by an economic combination, of the wealth which was withdrawn from society by another economic combination. In other words, through Political Economy to turn the theory of Property against Property in such a way as to engender what you German socialists call community and what I will limit myself for the moment to calling liberty or equality. | ” |

Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Bakunin, the father of modern anarchism, was a libertarian socialist, a theory by which the workers would directly manage the means of production through their own productive associations. There would be "equal means of subsistence, support, education, and opportunity for every child, boy or girl, until maturity, and equal resources and facilities in adulthood to create his own well-being by his own labor."[31]While many socialists emphasized the gradual transformation of society, most notably through the foundation of small, utopian communities, a growing number of socialists became disillusioned with the viability of this approach and instead emphasized direct political action. Early socialists were united, however, in their desire for a society based on cooperation rather than competition.

Marxism and the socialist movement

The French Revolution of 1789, Karl Marx and Frederick Engels wrote, "abolished feudal property in favour of bourgeois property".[32] The French Revolution was preceded and influenced by the works of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose Social Contract famously began, "Man is born free, and he is everywhere in chains."[33] Rousseau is credited with influencing socialist thought, but it was François-Noël Babeuf, and his Conspiracy of Equals, who is credited with providing a model for left-wing and communist movements of the 19th century.Marx and Engels drew from these socialist or communist ideas born in the French revolution, as well as from the German philosophy of GWF Hegel, and English political economy, particularly that of Adam Smith and David Ricardo. Marx and Engels developed a body of ideas which they called scientific socialism, more commonly called Marxism. Marxism comprised a theory of history (historical materialism) as well as a political, economic and philosophical theory.

In the Manifesto of the Communist Party, written in 1848 just days before the outbreak of the revolutions of 1848, Marx and Engels wrote, "The distinguishing feature of Communism is not the abolition of property generally, but the abolition of bourgeois property." Unlike those Marx described as utopian socialists, Marx determined that, "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles". While utopian socialists believed it was possible to work within or reform capitalist society, Marx confronted the question of the economic and political power of the capitalist class, expressed in their ownership of the means of producing wealth (factories, banks, commerce – in a word, 'Capital'). Marx and Engels formulated theories regarding the practical way of achieving and running a socialist system, which they saw as only being achieved by those who produce the wealth in society, the toilers, workers or "proletariat", gaining common ownership of their workplaces, the means of producing wealth.

Marx believed that capitalism could only be overthrown by means of a revolution carried out by the working class: "The proletarian movement is the self-conscious, independent movement of the immense majority, in the interest of the immense majority."[34] Marx believed that the proletariat was the only class with both the cohesion, the means and the determination to carry the revolution forward. Unlike the utopian socialists, who often idealised agrarian life and deplored the growth of modern industry, Marx saw the growth of capitalism and an urban proletariat as a necessary stage towards socialism.

For Marxists, socialism or, as Marx termed it, the first phase of communist society, can be viewed as a transitional stage characterized by common or state ownership of the means of production under democratic workers' control and management, which Engels argued was beginning to be realised in the Paris Commune of 1871, before it was overthrown.[35] Socialism to them is simply the transitional phase between capitalism and "higher phase of communist society". Because this society has characteristics of both its capitalist ancestor and is beginning to show the properties of communism, it will hold the means of production collectively but distributes commodities according to individual contribution.[36] When the socialist state (the dictatorship of the proletariat) naturally withers away, what will remain is a society in which human beings no longer suffer from alienation and "all the springs of co-operative wealth flow more abundantly." Here "society inscribe[s] on its banners: From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs!"[36] For Marx, a communist society entails the absence of differing social classes and thus the end of class warfare. According to Marx and Engels, once a socialist society had been ushered in, the state would begin to "wither away",[37] and humanity would be in control of its own destiny for the first time.

International Workingmen's Association (First International)

In Europe, harsh reaction followed the revolutions of 1848, during which ten countries had experienced brief or long-term social upheaval as groups carried out nationalist uprisings. After most of these attempts at systematic change ended in failure, conservative elements took advantage of the divided groups of socialists, anarchists, liberals, and nationalists, to prevent further revolt.[38] The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), also known as the First International, was founded in London in 1864. Victor Le Lubez, a French radical republican living in London, invited Karl Marx to come to London as a representative of German workers.[39] The IWA held a preliminary conference in 1865, and had its first congress at Geneva in 1866. Marx was appointed a member of the committee, and according to Saul Padover, Marx and Johann Georg Eccarius, a tailor living in London, became "the two mainstays of the International from its inception to its end".[39] The First International became the first major international forum for the promulgation of socialist ideas. In 1864 the International Workingmen's Association (sometimes called the "First International") united diverse revolutionary currents including French followers of Proudhon,[40] Blanquists, Philadelphes, English trade unionists, socialists and social democrats.In 1868, following their unsuccessful participation in the League of Peace and Freedom (LPF), Russian revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin and his collectivist anarchist associates joined the First International (which had decided not to get involved with the LPF).[41] They allied themselves with the federalist socialist sections of the International,[42] who advocated the revolutionary overthrow of the state and the collectivization of property.

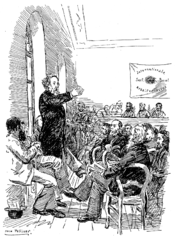

Mikhail Bakunin speaking to members of the IWA at the Basel Congress in 1869

At first, the collectivists worked with the Marxists to push the First International in a more revolutionary socialist direction. Subsequently, the International became polarised into two camps, with Marx and Bakunin as their respective figureheads.[43] Bakunin characterised Marx's ideas as centralist and predicted that, if a Marxist party came to power, its leaders would simply take the place of the ruling class they had fought against.[44][45] In 1872, the conflict climaxed with a final split between the two groups at the Hague Congress, where Bakunin and James Guillaume were expelled from the International and its headquarters were transferred to New York. In response, the federalist sections formed their own International at the St. Imier Congress, adopting a revolutionary anarchist program.[46]

Paris Commune

Barricades Boulevard Voltaire, Paris during the uprising known as the Paris Commune

According to Marx and Engels, for a few weeks the Paris Commune provided a glimpse of a socialist society, before it was brutally suppressed by the French government.

From the outset the Commune was compelled to recognize that the working class, once come to power, could not manage with the old state machine; that in order not to lose again its only just conquered supremacy, this working class must, on the one hand, do away with all the old repressive machinery previously used against it itself, and, on the other, safeguard itself against its own deputies and officials, by declaring them all, without exception, subject to recall at any moment.Following the 1871 Paris Commune, the socialist movement, as the whole of the workers' movement, was decapitated and deeply affected for years.

— Engels' 1891 postscript to The Civil War In France by Karl Marx[48]

The Second International

As the ideas of Marx and Engels took on flesh, particularly in central Europe, socialists sought to unite in an international organisation. In 1889, on the centennial of the French Revolution of 1789, the Second International was founded, with 384 delegates from 20 countries representing about 300 labour and socialist organizations.[49] Anarchists were ejected and not allowed in mainly because of the pressure from marxists.[50]Just before his death in 1895, Engels argued that there was now a "single generally recognised, crystal clear theory of Marx" and a "single great international army of socialists". Despite its illegality due to the Anti-Socialist Laws of 1878, the Social Democratic Party of Germany's use of the limited universal male suffrage were "potent" new methods of struggle which demonstrated their growing strength and forced the dropping of the Anti-Socialist legislation in 1890, Engels argued.[51] In 1893, the German SPD obtained 1,787,000 votes, a quarter of votes cast. However, before the leadership of the SPD published Engels' 1895 Introduction to Marx's Class Struggles in France 1848–1850, they removed certain phrases they felt were too revolutionary.[52]

Marx believed that it was possible to have a peaceful socialist transformation in England, although the British ruling class would then revolt against such a victory.[53] America and the Netherlands might also have a peaceful transformation, but not in France, where Marx believed there had been "perfected... an enormous bureaucratic and military organisation, with its ingenious state machinery" which must be forcibly overthrown. However, eight years after Marx's death, Engels argued that it was possible to achieve a peaceful socialist revolution in France, too.[54]

Germany

The SPD was by far the most powerful of the social democratic parties. Its votes reached 4.5 million, it had 90 daily newspapers, together with trade unions and co-ops, sports clubs, a youth organization, a women's organization and hundreds of full-time officials. Under the pressure of this growing party, Bismarck introduced limited welfare provision and working hours were reduced. Germany experienced sustained economic growth for more than forty years. Commentators suggest that this expansion, together with the concessions won, gave rise to illusions amongst the leadership of the SPD that capitalism would evolve into socialism gradually.Beginning in 1896, in a series of articles published under the title "Problems of socialism", Eduard Bernstein argued that an evolutionary transition to socialism was both possible and more desirable than revolutionary change. Bernstein and his supporters came to be identified as "revisionists" because they sought to revise the classic tenets of Marxism. Although the orthodox Marxists in the party, led by Karl Kautsky, retained the Marxist theory of revolution as the official doctrine of the party, and it was repeatedly endorsed by SPD conferences, in practice the SPD leadership became increasingly reformist.

Russia

Bernstein coined the aphorism: "The movement is everything, the final goal nothing". But the path of reform appeared blocked to the Russian Marxists while Russia remained the bulwark of reaction. In the preface to the 1882 Russian edition to the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels had saluted the Russian Marxists who, they said, "formed the vanguard of revolutionary action in Europe". But the working class, although many were organised in vast modern western-owned enterprises, comprised no more than a small percentage of the population and "more than half the land is owned in common by the peasants". Marx and Engels posed the question: How was Russia to progress to socialism? Could Russia "pass directly" to socialism or "must it first pass through the same process" of capitalist development as the West? They replied: "If the Russian Revolution becomes the signal for a proletarian revolution in the West, so that both complement each other, the present Russian common ownership of land may serve as the starting point for a communist development."[55]In 1903, the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party began to split on ideological and organizational questions into Bolshevik ('Majority') and Menshevik ('Minority') factions, with Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin leading the more radical Bolsheviks. Both wings accepted that Russia was an economically backward country unripe for socialism. The Mensheviks awaited the capitalist revolution in Russia. But Lenin argued that a revolution of the workers and peasants would achieve this task. After the Russian revolution of 1905, Leon Trotsky argued that unlike the French revolution of 1789 and the European Revolutions of 1848 against absolutism, the capitalist class would never organise a revolution in Russia to overthrow absolutism, and that this task fell to the working class who, liberating the peasantry from their feudal yoke, would then immediately pass on to the socialist tasks and seek a "permanent revolution" to achieve international socialism.[56] Assyrian nationalist Freydun Atturaya tried to create regional self-government for the Assyrian people with the socialism ideology. He even wrote the Urmia Manifesto of the United Free Assyria. However, his attempt was put to an end by Russia.

United States

In 1877, the Socialist Labor Party of America was founded. This party, which advocated Marxism and still exists today, was a confederation of small Marxist parties and came under the leadership of Daniel De Leon. In 1901, a merger between opponents of De Leon and the younger Social Democratic Party joined with Eugene V. Debs to form the Socialist Party of America. In 1905, the Industrial Workers of the World formed from several independent labor unions. The IWW opposed the political means of Debs and De Leon, as well as the craft unionism of Samuel Gompers. In 1910, the Sewer Socialists, the main group of American socialists, elected Victor Berger as a socialist Congressman and Emil Seidel as a socialist mayor of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, most of the other elected city officials being socialist as well. This Socialist Party of America grew to 150,000 in 1912 and polled 897,000 votes in the presidential campaign of that year, 6 percent of the total vote. Socialist mayor Daniel Hoan, was elected in 1916 and stayed in office until 1940. The final Socialist mayor, Frank P. Zeidler, was elected in 1948 and served three terms, ending in 1960. Milwaukee remained the hub of Socialism during these years. The Socialist Party declined after the First World War. By the 1880s anarcho-communism was already present in the United States as can be seen in the publication of the journal Freedom: A Revolutionary Anarchist-Communist Monthly by Lucy Parsons and Lizzy Holmes.[57] Around that time these American anarcho-communist sectors entered in debate with the individualist anarchist group around Benjamin Tucker.[58]France

French socialism was beheaded by the suppression of the Paris commune (1871), its leaders killed or exiled. But in 1879, at the Marseille Congress, workers' associations created the Federation of the Socialist Workers of France. Three years later, Jules Guesde and Paul Lafargue, the son-in-law of Karl Marx, left the federation and founded the French Workers' Party.The Federation of the Socialist Workers of France was termed "possibilist" because it advocated gradual reforms, whereas the French Workers' Party promoted Marxism. In 1905 these two trends merged to form the French Section Française de l'Internationale Ouvrière (SFIO), led by Jean Jaurès and later Léon Blum. In 1906 it won 56 seats in Parliament. The SFIO adhered to Marxist ideas but became, in practice, a reformist party. By 1914 it had more than 100 members in the Chamber of Deputies.

World War I

Further information: Internationalist/Defencist Schism

When World War I began in 1914, many European socialist leaders

supported their respective governments' war aims. The social democratic

parties in the UK, France, Belgium and Germany supported their

respective state's wartime military and economic planning, discarding

their commitment to internationalism and solidarity.Lenin, in his April Theses, denounced the war as an imperialist conflict, and urged workers worldwide to use it as an occasion for proletarian revolution. The Second International dissolved during the war, while Lenin, Trotsky, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, together with a small number of other Marxists opposed to the war, came together in the Zimmerwald Conference in September 1915.

Anarchism

Main article: History of anarchism

Anarchism as a social movement

has regularly endured fluctuations in popularity. Its classical period,

which scholars demarcate as from 1860 to 1939, is associated with the

working-class movements of the 19th century and the Spanish Civil War-era struggles against fascism.[59]

Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin opposed the Marxist

aim of dictatorship of the proletariat in favour of universal

rebellion, and allied himself with the federalists in the First

International before his expulsion by the Marxists.[60]

The anti-authoritarian sections of the First International were the precursors of the anarcho-syndicalists, seeking to "replace the privilege and authority of the State" with the "free and spontaneous organization of labor."[64]

In 1907, the International Anarchist Congress of Amsterdam gathered delegates from 14 different countries, among which important figures of the anarchist movement, including Errico Malatesta, Pierre Monatte, Luigi Fabbri, Benoît Broutchoux, Emma Goldman, Rudolf Rocker, and Christiaan Cornelissen. Various themes were treated during the Congress, in particular concerning the organisation of the anarchist movement, popular education issues, the general strike or antimilitarism. A central debate concerned the relation between anarchism and syndicalism (or trade unionism). The Spanish Workers Federation in 1881 was the first major anarcho-syndicalist movement; anarchist trade union federations were of special importance in Spain. The most successful was the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (National Confederation of Labour: CNT), founded in 1910. Before the 1940s, the CNT was the major force in Spanish working class politics, attracting 1.58 million members at one point and playing a major role in the Spanish Civil War.[65] The CNT was affiliated with the International Workers Association, a federation of anarcho-syndicalist trade unions founded in 1922, with delegates representing two million workers from 15 countries in Europe and Latin America.

Some anarchists, such as Johann Most, advocated publicizing violent acts of retaliation against counter-revolutionaries because "we preach not only action in and for itself, but also action as propaganda."[66] Numerous heads of state were assassinated between 1881 and 1914 by members of the anarchist movement. For example, U.S. President McKinley's assassin Leon Czolgosz claimed to have been influenced by anarchist and feminist Emma Goldman.

Anarchists participated alongside the Bolsheviks in both February and October revolutions, and were initially enthusiastic about the Bolshevik coup.[67] However, the Bolsheviks soon turned against the anarchists and other left-wing opposition, a conflict that culminated in the 1921 Kronstadt rebellion which the new government repressed. Anarchists in central Russia were either imprisoned, driven underground or joined the victorious Bolsheviks; the anarchists from Petrograd and Moscow fled to the Ukraine.[68] There, in the Free Territory, they fought in the civil war against the Whites (a Western-backed grouping of monarchists and other opponents of the October Revolution) and then the Bolsheviks as part of the Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine led by Nestor Makhno, who established an anarchist society in the region for a number of months.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the rise of fascism in Europe transformed anarchism's conflict with the state.

In Spain, the CNT initially refused to join a popular front electoral alliance, and abstention by CNT supporters led to a right wing election victory. But in 1936, the CNT changed its policy and anarchist votes helped bring the popular front back to power. Months later, the former ruling class responded with an attempted coup causing the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939).[69] In response to the army rebellion, an anarchist-inspired movement of peasants and workers, supported by armed militias, took control of Barcelona and of large areas of rural Spain where they collectivised the land.[70] But even before the fascist victory in 1939, the anarchists were losing ground in a bitter struggle with the Stalinists, who controlled the distribution of military aid to the Republican cause from the Soviet Union. Stalinist-led troops suppressed the collectives and persecuted both dissident Marxists and anarchists.[71]

A surge of popular interest in anarchism occurred during the 1960s and 1970s.[72] In 1968 in Carrara, Italy the International of Anarchist Federations was founded during an international Anarchist conference in Carrara in 1968 by the three existing European federations of France, the Italian and the Iberian Anarchist Federation as well as the Bulgarian federation in French exile.[73][74] In the United Kingdom this was associated with the punk rock movement, as exemplified by bands such as Crass and the Sex Pistols.[75] The housing and employment crisis in most of Western Europe led to the formation of communes and squatter movements like that of Barcelona, Spain. In Denmark, squatters occupied a disused military base and declared the Freetown Christiania, an autonomous haven in central Copenhagen.

Since the revival of anarchism in the mid 20th century,[76] a number of new movements and schools of thought emerged.

Around the turn of the 21st century, anarchism grew in popularity and influence as part of the anti-war, anti-capitalist, and anti-globalisation movements.[77] Anarchists became known for their involvement in protests against the meetings of the World Trade Organization (WTO), Group of Eight, and the World Economic Forum. Some anarchist factions at these protests engaged in rioting, property destruction, and violent confrontations with police, and the confrontations were selectively portrayed in mainstream media coverage as violent riots. These actions were precipitated by ad hoc, leaderless, anonymous cadres known as black blocs; other organisational tactics pioneered in this time include security culture, affinity groups and the use of decentralised technologies such as the internet.[77] A landmark struggle of this period was the confrontations at WTO conference in Seattle in 1999.[77]

International anarchist federations in existence include the International of Anarchist Federations, the International Workers' Association, and International Libertarian Solidarity.

Social democracy to 1917

The Social Democratic Party (SPD) in Germany became the largest and most powerful socialist party in Europe, despite working illegally until the anti-socialist laws were dropped in 1890. In the 1893 elections it gained 1,787,000 votes, a quarter of the total votes cast, according to Engels. In 1895, the year of his death, Engels emphasised the Communist Manifesto's emphasis on winning, as a first step, the "battle of democracy".[78] Since the 1866 introduction of universal male franchise the SPD had proved that old methods of, "surprise attacks, of revolutions carried through by small conscious minorities at the head of masses lacking consciousness is past". Marxists, Engels emphasised, must "win over the great mass of the people" before initiating a revolution.[79]Marx believed that it was possible to have a peaceful socialist revolution in England, America and the Netherlands, but not in France, where he believed there had been "perfected ... an enormous bureaucratic and military organisation, with its ingenious state machinery" which must be forcibly overthrown. However, eight years after Marx's death, Engels regarded it possible to achieve a peaceful socialist revolution in France, too.[54]

In 1896, Eduard Bernstein argued that once full democracy had been achieved, a transition to socialism by gradual means was both possible and more desirable than revolutionary change. Bernstein and his supporters came to be identified as "revisionists", because they sought to revise the classic tenets of Marxism. Although the orthodox Marxists in the party, led by Karl Kautsky, retained the Marxist theory of revolution as the official doctrine of the party, and it was repeatedly endorsed by SPD conferences, in practice the SPD leadership became more and more reformist.

In Europe most Social Democratic parties participated in parliamentary politics and the day-to-day struggles of the trade unions. In the UK, however, many trade unionists who were members of the Social Democratic Federation, which included at various times future trade union leaders such as Will Thorne, John Burns and Tom Mann, felt that the Federation neglected the industrial struggle. Along with Engels, who refused to support the SDF, many felt that dogmatic approach of the SDF, particularly of its leader, Henry Hyndman, meant that it remained an isolated sect. The mass parties of the working class under social democratic leadership became more reformist and lost sight of their revolutionary objective. Thus the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO), founded in 1905, under Jean Jaurès and later Léon Blum adhered to Marxist ideas, but became in practice a reformist party.

In some countries, particularly Britain and the British dominions, labour parties were formed. These were parties largely formed by and controlled by the trade unions, rather than formed by groups of socialist activists who then appealed to the workers for support. In Britain, the Labour Party, (at first the Labour Representation Committee) was established by representatives of trade unions together with affiliated socialist parties, principally the Independent Labour Party but also for a time the avowedly Marxist Social Democratic Federation and other groups, such as the Fabians. On 1 December 1899 Anderson Dawson of the Australian Labor Party became the Premier of Queensland, Australia, forming the world's first parliamentary socialist government . The Dawson government, however, lasted only one week, being defeated at the first sitting of parliament.

The British Labour Party first won seats in the House of Commons in 1902. It won the majority of the working class away from the Liberal Party after World War I. In Australia, the Labor Party achieved rapid success, forming its first national government in 1904. Labour parties were also formed in South Africa and New Zealand but had less success. The British Labour Party adopted a specifically socialist constitution (‘Clause four, Part four’) in 1918.

The strongest opposition to revisionism came from socialists in countries such as the Russian Empire where parliamentary democracy did not exist. Chief among these was the Russian Vladimir Lenin, whose works such as Our Programme (1899) set out the views of those who rejected revisionist ideas. In 1903, there was the beginnings of what eventually became a formal split in the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party into revolutionary Bolshevik and reformist Menshevik factions.

In 1914, the outbreak of World War I led to a crisis in European socialism. The parliamentary leaderships of the socialist parties of Germany, France, Belgium and Britain each voted to support the war aims of their country's governments, although some leaders, like Ramsay MacDonald in Britain and Karl Liebknecht in Germany, opposed the war from the start. Lenin, in exile in Switzerland, called for revolutions in all the combatant states as the only way to end the war and achieve socialism. Lenin, Leon Trotsky, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, together with a small number of other Marxists opposed to the war, came together in the Zimmerwald Conference in September 1915. This conference saw the beginning of the end of the uneasy coexistence of revolutionary socialists with the social democrats, and by 1917 war-weariness led to splits in several socialist parties, notably the German Social Democrats.

The Russian Revolution of October 1917 led to a withdrawal from World War I, one of the principal demands of the Russian revolution, as the Soviet government immediately sued for peace. Germany and the former allies invaded the new Soviet Russia, which had repudiated the former Romanov regime's national debts and nationalized the banks and major industry. Russia was the only country in the world where socialists had taken power, and it appeared to many socialists to confirm the ideas, strategy and tactics of Lenin and Trotsky.

The inter-war era and World War II

The Russian Revolution of October 1917 brought about the definitive ideological division between Communists as denoted with a capital "C" on the one hand and other communist and socialist trends such as anarcho-communists and social democrats, on the other. The Left Opposition in the Soviet Union gave rise to Trotskyism which was to remain isolated and insignificant for another fifty years, except in Sri Lanka where Trotskyism gained the majority and the pro-Moscow wing was expelled from the Communist Party.In 1922, the fourth congress of the Communist International took up the policy of the United Front, urging Communists to work with rank and file Social Democrats while remaining critical of their leaders, who they criticised for "betraying" the working class by supporting the war efforts of their respective capitalist classes. For their part, the social democrats pointed to the dislocation caused by revolution, and later, the growing authoritarianism of the Communist Parties. When the Communist Party of Great Britain applied to affiliate to the Labour Party in 1920 it was turned down.

Revolutionary socialism and the Soviet Union (1917-39)

After three years, the First World War, at first greeted with enthusiastic patriotism, produced an upsurge of radicalism in most of Europe and also as far afield as the United States (see Socialism in the United States) and Australia. In the Russian revolution of February 1917, workers' councils (in Russian, soviets) had been formed, and Lenin and the Bolsheviks called for "All power to the Soviets". After the October 1917 Russian revolution, led by Lenin and Trotsky, consolidated power in the Soviets, Lenin declared "Long live the world socialist revolution!"[80] Briefly in Soviet Russia socialism was not just a vision of a future society, but a description of an existing one. The Soviet regime began to bring all the means of production (except agricultural production) under state control, and implemented a system of government through the workers' councils or soviets.The initial success of the Russian Revolution inspired other revolutionary parties to attempt the same thing unleashing the Revolutions of 1917-23. In the chaotic circumstances of postwar Europe, with the socialist parties divided and discredited, Communist revolutions across Europe seemed a possibility. Communist parties were formed, often from minority or majority factions in most of the world's socialist parties, which broke away in support of the Leninist model.

The German Revolution of 1918 overthrew the old absolutism and, like Russia, set up Workers' and Soldiers' Councils almost entirely made up of SPD and Independent Social Democrats (USPD) members. The Weimar republic was established and placed the SPD in power, under the leadership of Friedrich Ebert. Ebert agreed with Max von Baden that a social revolution was to be prevented and the state order must be upheld at any cost. In 1919 the Spartacist uprising challenged the power of the SPD government, but it was put down in blood and the German Communist leaders Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg were assassinated. Communist regimes briefly held power under Béla Kun in Hungary and under Kurt Eisner in Bavaria. There were further revolutionary movements in Germany until 1923, as well as in Vienna, and also in the industrial centres of northern Italy.

In this period few Communists doubted, least of all Lenin and Trotsky, that successful socialist revolutions carried out by the working classes of the most developed capitalist counties were essential to the success of the socialism, and therefore to the success of socialism in Russia in particular.[81] In March 1918, Lenin said, "we are doomed if the German revolution does not break out".[82] In 1919, the Communist Parties came together to form a 'Third International', termed the Communist International or Comintern. But the prolonged revolutionary period in Germany did not bring a socialist revolution.

A marxist current critical of the bolcheviks emerged and as such "Luxemburg’s workerism and spontaneism are exemplary of positions later taken up by the far-left of the period – Pannekoek, Roland Holst, and Gorter in the Netherlands, Sylvia Pankhurst in Britain, Gramsci in Italy, Lukacs in Hungary. In these formulations, the dictatorship of the proletariat was to be the dictatorship of a class, “not of a party or of a clique”."[83] However within this line of thought "The tension between anti-vanguardism and vanguardism has frequently resolved itself in two diametrically opposed ways: the first involved a drift towards the party; the second saw a move towards the idea of complete proletarian spontaneity...The first course is exemplified most clearly in Gramsci and Lukacs...The second course is illustrated in the tendency, developing from the Dutch and German far-lefts, which inclined towards the complete eradication of the party form."[83] In the emerging Soviet state there appeared Left-wing uprisings against the Bolsheviks which were a series of rebellions and uprisings against the Bolsheviks led or supported by left wing groups including Socialist Revolutionaries,[84] Left Socialist Revolutionaries, Mensheviks, and anarchists.[85] Some were in support of the White Movement while some tried to be an independent force. The uprisings started in 1918 and continued through the Russian Civil War and after until 1922. In response the Bolsheviks increasingly abandoned attempts to get these groups to join the government and suppressed them with force.

Within a few years a bureaucracy developed in Russia as a result of the Russian Civil War, foreign invasion, and Russia's historic poverty and backwardness. The bureaucracy undermined the democratic and socialist ideals of the Bolshevik Party and elevated Stalin to their leadership after Lenin's death. In order to consolidate power, the bureaucracy conducted a brutal campaign of lies and violence against the Left Opposition led by Trotsky.

By the mid 1920s, the impetus had gone out of the revolutionary forces in Europe and the national reformist socialist parties had regained their dominance over the working-class movement in most countries. The German Social Democrats held office for much of the 1920s, the British Labour Party formed its first government in 1924, and the French Socialists were also influential. In the Soviet Union, from 1924 Stalin pursued a policy of "socialism in one country". Trotsky argued that this approach was a shift away from the theory of Marx and Lenin, while others argued that it was a practical compromise fit for the times.

The postwar revolutionary upsurge provoked a powerful reaction from the forces of conservatism. Winston Churchill declared that Bolshevism must be "strangled in its cradle".[86] The invasion of Russia by the Allies, their trade embargo and backing for the White forces fighting against the Red Army in the civil war in the Soviet Union was cited by Aneurin Bevan, the leader of the left-wing in the Labour Party, as one of the causes of the Russian revolution's degeneration into dictatorship.[87] A "Red scare" in the United States was raised against the American Socialist Party of Eugene V. Debs and the Communist Party of America which arose after the Russian revolution from members who had broken from Debs' party. In Europe, fascist movements received significant funding, particularly from industrialists in heavy industry,[88][89] and came to power in Italy in 1922 under Benito Mussolini, and later in Germany in 1933, in Spain (1937) and Portugal, while strong fascist movements also developed in Hungary and Romania.

After 1929, with the Left Opposition legally banned and Trotsky exiled, Stalin led the Soviet Union into a what he termed a "higher stage of socialism." Agriculture was forcibly collectivised, at the cost of a massive famine and millions of deaths among the resistant peasantry. The surplus squeezed from the peasants was spent on a program of crash industrialisation, guided by the Communist Party through the Five Year Plan. This program produced some impressive results,[90] though at enormous human costs. Russia raised itself from an economically backward country to that of a superpower. Later Soviet development, however, particularly after the Second World War, was no faster than it was in Japan or the United States under capitalism. The use of resources, material and human, in the Soviet Union became very wasteful. Stalin's industrialization policy was geared towards the development of heavy industry, an emphasis that facilitated Soviet military action in its defence against Hitler's invasion during the Second World War in which the USSR stood on the side of the Allies of World War II. For "many Marxian libertarian socialists, the political bankruptcy of socialist orthodoxy necessitated a theoretical break. This break took a number of forms. The Bordigists and the SPGB championed a super-Marxian intransigence in theoretical matters. Other socialists made a return “behind Marx” to the anti-positivist programme of German idealism. Libertarian socialism has frequently linked its anti-authoritarian political aspirations with this theoretical differentiation from orthodoxy... Karl Korsch... remained a libertarian socialist for a large part of his life and because of the persistent urge towards theoretical openness in his work. Korsch rejected the eternal and static, and he was obsessed by the essential role of practice in a theory’s truth. For Korsch, no theory could escape history, not even Marxism. In this vein, Korsch even credited the stimulus for Marx’s Capital to the movement of the oppressed classes. "[83]

The Soviet achievement in the 1930s seemed hugely impressive from the outside, and convinced many people, not necessarily Communists or even socialists, of the virtues of state planning and authoritarian models of social development. This was later to have important consequences in countries like China, India and Egypt, which tried to copy some aspects of the Soviet model. It also won large sections of the western intelligentsia over to a pro-Soviet view, to the extent that many were willing to ignore or excuse such events as Stalin's Great Purge of 1936-38, in which millions of people died.

The Great Depression, which began in 1929, seemed to socialists and Communists everywhere to be the final proof of the bankruptcy, literally as well as politically, of capitalism. But socialists were unable to take advantage of the Depression to either win elections or stage revolutions. Labor governments in Britain and Australia were disastrous failures. In the United States, the liberalism of President Franklin D. Roosevelt won mass support and deprived socialists of any chance of gaining ground. And in Germany it was the fascists of Adolf Hitler's Nazi Party who successfully exploited the Depression to win power, in January 1933.

Hitler's regime swiftly destroyed both the German Communist Party and the Social Democratic Party, the worst blow the world socialist movement had ever suffered. This forced Stalin to reassess his strategy, and from 1935 the Comintern began urging a Popular Front against fascism. The socialist parties were at first suspicious, given the bitter hostility of the 1920s, but eventually effective Popular Fronts were formed in both France and Spain. After the election of a Popular Front government in Spain in 1936 a fascist military revolt led to the Spanish Civil War. The crisis in Spain also brought down the Popular Front government in France under Léon Blum. Ultimately the Popular Fronts were not able to prevent the spread of fascism or the aggressive plans of the fascist powers. Trotskyists considered Popular Fronts a "strike breaking conspiracy"[91] and considered them an impediment to successful resistance to fascism.

When Stalin consolidated his power in the Soviet Union in the late 1920s, Trotsky was forced into exile, eventually residing in Mexico. He maintained active in organizing the Left Opposition internationally, which worked within the Comintern to gain new members. Some leaders of the Communist Parties sided with Trotsky, such as James P. Cannon in the United States. They found themselves expelled by the Stalinist Parties and persecuted by both GPU agents and the political police in Britain, France, the United States, China, and all over the world. Trotskyist parties had a large influence in Sri Lanka and Bolivia.

In 1938, Trotsky and his supporters founded a new international organisation of dissident communists, the Fourth International. In his Results and Prospects and Permanent Revolution Trotsky developed a theory of revolution uninterrupted by the stagism of Stalinist orthodoxy. He argued that Russia was a bureaucratically degenerated workers state in his work The Revolution Betrayed, where he predicted that if a political revolution of the working class did not overthrow Stalinism, the Stalinist bureaucracy would resurrect capitalism. Trotsky's monumental History of the Russian Revolution is considered a work of primary importance by Trotsky's followers.

Britain

Once the world's most powerful nation, Britain avoided a revolution during the period of 1917–1923 but was significantly affected by revolt. The Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, had promised the troops in the 1918 election that his Conservative-led coalition would make post-war Britain "a fit land for heroes to live in". But many demobbed troops complained of chronic unemployment and suffered low pay, disease and poor housing.[92]In 1918, the Labour Party adopted as its aim to secure for the workers, "the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange". In 1919, the Miners Federation, whose Members of Parliament pre-dated the formation of the Labour Party and were since 1906 a part of that body, demanded the withdrawal of British troops from Soviet Russia. The 1919 Labour Party conference voted to discuss the question of affiliation to the Third (Communist) International, "to the distress of its leaders".[93] A vote was won committing the Labour Party committee of the Trades Union Congress to arrange "direct industrial action" to "stop capitalist attacks upon the Socialist Republics of Russia and Hungary."[94] The threat of immediate strike action forced the Conservative-led coalition government to abandon its intervention in Russia.[95]

In 1914 the unions of the transport workers, the mine workers and the railway workers had formed a Triple Alliance. In 1919, Lloyd George sent for the leaders of the Triple Alliance, one of whom was miner's leader Robert Smillie, a founder member of the Independent Labour Party in 1889 who was to become a Labour Party MP in the first 1924 Labour government. According to Smillie, Lloyd George said:

Gentlemen, you have fashioned, in the Triple Alliance of the unions represented by you, a most powerful instrument. I feel bound to tell you that in our opinion we are at your mercy. The Army is disaffected and cannot be relied upon. Trouble has occurred already in a number of camps. We have just emerged from a great war and the people are eager for the reward of their sacrifices, and we are in no position to satisfy them. In these circumstances, if you carry out your threat and strike, then you will defeat us. But if you do so, have you weighed the consequences? The strike will be in defiance of the government of the country and by its very success will precipitate a constitutional crisis of the first importance. For, if a force arises in the state which is stronger than the state itself, then it must be ready to take on the functions of the state, or withdraw and accept the authority of the state. Gentlemen, have you considered, and if you have, are you ready?"From that moment on", Smillie conceded to Aneurin Bevan, "we were beaten and we knew we were". When the UK General Strike of 1926 broke out, the trade union leaders, "had never worked out the revolutionary implications of direct action on such a scale", Bevan says.[97] Bevan was a member of the Independent Labour Party and one of the leaders of the South Wales miners during the strike. The TUC called off the strike after nine days. In the North East of England and elsewhere, "councils of action" were set up, with many rank and file Communist Party members often playing a critical role. The councils of action took control of essential transport and other duties.[98] When the strike ended, the miners were locked out and remained locked out for six months. Bevan became a Labour MP in 1929.

— Aneurin Bevan, In Place of Fear[96]

In January 1924, the Labour Party formed a minority government for the first time with Ramsay MacDonald as prime minister. The Labour Party intended to ratify an Anglo-Russian trade agreement, which would break the trade embargo on Russia. This was attacked by the Conservatives and new elections took place in October 1924. Four days before polling day the Daily Mail published the Zinoviev letter, a forgery that claimed the Labour Party had links with Soviet Communists and was secretly fomenting revolution. The fears instilled by the press of a Labour Party in secret Communist manoeuvres, together with the half-hearted "respectable" policies pursued by MacDonald, led to Labour losing the October 1924 general election. The victorious Conservatives repudiated the Anglo-Soviet treaty.

The leadership of the Labour Party, like social democratic parties almost everywhere, (with the exception of Sweden and Belgium), tried to pursue a policy of moderation and economic orthodoxy. At times of depression this policy was not popular with the Labour Party's working class supporters. The influence of Marxism grew in the Labour Party during the inter-war years. Anthony Crosland argued in 1956 that under the impact of the 1931 slump and the growth of fascism, the younger generation of left-wing intellectuals for the most part "took to Marxism" including the "best-known leaders" of the Fabian tradition, Sidney and Beatrice Webb. The Marxist Professor Harold Laski, who was to be chairman of the Labour Party in 1945-6, was the "outstanding influence" in the political field.[99]

The Marxists within the Labour Party differed in their attitude to the Communists. Some were uncitical and some were expelled as "fellow travellers", while in the 1930s others were Trotskyists and sympathisers working inside the Labour Party, especially in its youth wing where they were influential.

In the general election of 1929 the Labour Party won 288 seats out of 615 and formed another minority government. The depression of that period brought high unemployment and Prime Minister MacDonald sought to make cuts in order to balance the budget. The trade unions opposed MacDonald's proposed cuts and he split the Labour government to form the National Government of 1931. This experience moved the Labour Party leftward, and at the start of the Second World War an official Labour Party pamphlet written by Harold Laski argued that, "the rise of Hitler and the methods by which he seeks to maintain and expand his power are deeply rooted in the economic and social system of Europe... economic nationalism, the fight for markets, the destruction of political democracy, the use of war as an instrument of national policy":

The war will leave its meed[100] of great problems, problems of internal social organisation... Business men and aristocrats, the old ruling classes of Europe, had their chance from 1919 to 1939; they failed to take advantage of it. They rebuilt the world in the image of their own vested interests... The ruling class has failed; this war is the proof of it. The time has come to give the common people the right to become the master of their own destiny... Capitalism has been tried; the results of its power are before us today. Imperialism has been tried; it is the foster-parent of this great agony. Given power [the Labour Party] will seek, as no other Party will seek, the basic transformation of our society. It will replace the profit-seeking motive by the motive of public service... there is now no prospect of domestic well-being or of international peace except in Socialism.

— Harold Laski, The Labour Party, the War and the Future (1939)[101]

United States

After embracing anarchism Albert Parsons turned his activity to the growing movement to establish the 8-hour day. In January 1880, the Eight-Hour League of Chicago sent Parsons to a national conference in Washington, DC, a gathering which launched a national lobbying movement aimed at coordinating efforts of labor organizations to win and enforce the 8-hour workday.[102] In the fall of 1884, Parsons launched a weekly anarchist newspaper in Chicago, The Alarm.[103] The first issue was dated October 4, 1884, and was produced in a press run of 15,000 copies.[104] The publication was a 4-page broadsheet with a cover price of 5 cents. The Alarm listed the International Working People's Association as its publisher and touted itself as "A Socialistic Weekly" on its page 2 masthead.[105] On May 1, 1886, Parsons, with his wife Lucy Parsons and two children, led 80,000 people down Michigan Avenue, in what is regarded as the first-ever May Day Parade, in support of the eight-hour work day. Over the next few days 340,000 laborers joined the strike. Parsons, amidst the May Day Strike, found himself called to Cincinnati, where 300,000 workers had struck that Saturday afternoon. On that Sunday he addressed the rally in Cincinnati of the news from the "storm center" of the strike and participated in a second huge parade, led by 200 members of The Cincinnati Rifle Union, with certainty that victory was at hand. In 1886, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions (FOTLU) of the United States and Canada unanimously set 1 May 1886, as the date by which the eight-hour work day would become standard.[106] In response, unions across the United States prepared a general strike in support of the event.[106] On 3 May, in Chicago, a fight broke out when strikebreakers attempted to cross the picket line, and two workers died when police opened fire upon the crowd.[107] The next day, 4 May, anarchists staged a rally at Chicago's Haymarket Square.[108] A bomb was thrown by an unknown party near the conclusion of the rally, killing an officer.[109] In the ensuing panic, police opened fire on the crowd and each other.[110] Seven police officers and at least four workers were killed.[111] Eight anarchists directly and indirectly related to the organisers of the rally were arrested and charged with the murder of the deceased officer. The men became international political celebrities among the labour movement. Four of the men were executed and a fifth committed suicide prior to his own execution. The incident became known as the Haymarket affair, and was a setback for the labour movement and the struggle for the eight-hour day. In 1890 a second attempt, this time international in scope, to organise for the eight-hour day was made. The event also had the secondary purpose of memorializing workers killed as a result of the Haymarket affair.[112] Although it had initially been conceived as a once-off event, by the following year the celebration of International Workers' Day on May Day had become firmly established as an international worker's holiday.[106] Albert Parsons is best remembered as one of four Chicago radical leaders convicted of conspiracy and hanged following a bomb attack on police remembered as the Haymarket affair. Emma Goldman, the activist and political theorist, was attracted to anarchism after reading about the incident and the executions, which she later described as "the events that had inspired my spiritual birth and growth." She considered the Haymarket martyrs to be "the most decisive influence in my existence".[113] Her associate, Alexander Berkman also described the Haymarket anarchists as "a potent and vital inspiration."[114] Others whose commitment to anarchism crystallized as a result of the Haymarket affair included Voltairine de Cleyre and "Big Bill" Haywood, a founding member of the Industrial Workers of the World.[114] Goldman wrote to historian, Max Nettlau, that the Haymarket affair had awakened the social consciousness of "hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people".[115]In the Presidential election of 1912, Eugene V. Debs received 5.99% of the popular vote (a total of 901,551 votes), while his total of 913,693 votes in the 1920 campaign, although smaller percentage-wise, remains the all-time high for a Socialist Party candidate in the United States.[116]

In the United States, the Communist Party USA was formed in 1919 from former adherents of the Socialist Party of America. One of the founders, James Cannon, later became the leader of Trotskyist forces outside the Soviet Union. The Great Depression began in the US on Black Tuesday, October 29, 1929. Unemployment rates passed 25%, prices and incomes fell 20–50%, but the debts remained at the same dollar amount. 9,000 banks failed during the decade of the 30s. By 1933, depositors saw $140 billion of their deposits disappear due to uninsured bank failures.[117]

Workers organized against their deteriorating conditions and socialists played a critical role. In 1934 the Minneapolis Teamsters Strike led by the Trotskyist Communist League of America, the West Coast Longshore Strike led by the Communist Party USA, and the Toledo Auto-Lite Strike led by the American Workers Party, played an important role in the formation of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in the USA.

In Minnesota, the General Drivers Local 574 of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters struck, despite an attempt to block the vote by AFL officials, demanding union recognition, increased wages, shorter hours, overtime rates, improved working conditions and job protection through seniority. In the battles that followed, which captured country-wide media attention, three strikes took place, martial law was declared and the National Guard was sent in. Two strikers were killed. Protest rallies of 40,000 were held. Farrell Dobbs, who became the leader of the local, had at the outset joined the "small and poverty-stricken" Communist League of America, founded by James P. Cannon and others in 1928 after their expulsion from the Communist Party USA for Trotskyism.[118]

Success for the CIO quickly followed its formation. In 1937, one of the founding unions of the CIO, the United Auto Workers, won union recognition at General Motors Corporation after a tumultuous forty-four day sit-down strike, while the Steel Workers Organizing Committee, which was formed by the CIO, won a collective bargaining agreement with U.S. Steel. The CIO merged with the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in 1955 becoming the AFL-CIO.

Germany

In 1928, the Communist International, now fully under the leadership of Stalin, turned from the united front policy to an ultra-left policy of the Third Period, a policy of aggressive confrontation of social democracy. This divided the working class at a critical time.Like the Labour Party in the UK, the Social Democratic Party in Germany, which was in power in 1928, followed an orthodox deflationary policy and pressed for reductions in unemployment benefits in order to save taxes and reduce budget deficits. These policies did not halt the recession and the government resigned.

The Communists described the Social Democratic leaders as "social fascists" and in the Prussian Landtag they voted with the Nazis to bring down the Social Democratic government. Fascism continued to grow, with powerful backing from industrialists, especially in heavy industry, and Hitler was invited into power in 1933.

Hitler's regime swiftly destroyed both the German Communist Party and the Social Democratic Party, the worst blow the world socialist movement had ever suffered. This forced Stalin to reassess his strategy, and from 1935 the Comintern began urging the formation of Popular Fronts, which were to include not just the Social Democratic parties but critically also "progressive capitalist" parties which were wedded to a capitalist policy.

After the election of a Popular Front government in Spain in 1936 a fascist military revolt led to the Spanish Civil War. The crisis in Spain brought down the Popular Front government in France under Léon Blum. Ultimately the Popular Fronts were not able to prevent the spread of fascism or the aggressive plans of the fascist powers. Trotskyists considered Popular Fronts a "strike breaking conspiracy", an impediment to successful resistance to fascism due to their inclusion of pro-capitalist parties which demanded policies of opposition to strikes and workers’ actions against the capitalist class.[91]

Sweden

The Swedish Socialists formed a government in 1932. They broke with economic orthodoxy during the depression and carried out extensive public works financed from government borrowing. They emphasised large-scale intervention and the high unemployment they had inherited was eliminated by 1938. Their success encouraged the adoption of Keynesian policies of deficit financing pursued by almost all Western countries after World War II.Spain

During the Spanish Civil War, anarchists set up different forms of cooperative and communal arrangements, especially in the rural areas of Aragon and Catalonia. However, these communes were disbanded by the Popular Front government.[119]Israel

Jewish Zionists established utopian socialist communities in Palestine, which were known as kibbutzim, a small number of which still survive.[120]The Post-war era (1945-85)

In the 1930s, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), a reformist socialist political party that was up to then based upon revisionist Marxism, began a transition away from Marxism towards liberal socialism beginning in the 1930s. After the party was banned by the Nazi regime in 1933, the SPD acted in exile through the Sopade. In 1934 the Sopade began to publish material that indicated that the SPD was turning towards liberal socialism.[121] Sopade member Curt Geyer was a prominent proponent of liberal socialism within the Sopade, and declared that Sopade represented the tradition of Weimar Republic social democracy — liberal democratic socialism, and declared that Sopade's held true to its mandate of traditional liberal principles combined with the political realism of socialism.[122] After the restoration of democracy in West Germany, The SPD's Godesberg Program in 1959 eliminated the party's remaining Marxist-aligned policies. The SPD then became officially based upon freiheitlicher Sozialismus (liberal socialism).[123] West German Chancellor Willy Brandt has been identified as a liberal socialist.[124]In 1945, the world's three great powers met at the Yalta Conference to negotiate an amicable and stable peace. UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill joined USA President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee. With the relative decline of Britain compared to the two superpowers, the USA and the Soviet Union, however, many viewed the world as "bi-polar" – a world with two irreconcilable and antagonistic political and economic systems.[citation needed]

As a result of the failure of the Popular Fronts and the inability of Britain and France to conclude a defensive alliance against Hitler, Stalin again changed his policy in August 1939 and signed a non-aggression pact, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, with Nazi Germany. Shortly afterwards World War II broke out, and within two years Hitler had occupied most of Europe, and by 1942 both democracy and social democracy in central Europe fell under the threat of fascism. The only socialist parties of any significance able to operate freely were those in Britain, Sweden, Switzerland, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. But the entry of the Soviet Union into the war in 1941 marked the turning of the tide against fascism, and as the German armies retreated another great upsurge in left-wing sentiment swelled up in their wake. The resistance movements against German occupation were mostly led by socialists and communists, and by the end of the war the parties of the left were greatly strengthened.

One of the great postwar victories of democratic socialism was the election victory of the British Labour Party led by Clement Attlee in June 1945. Socialist (and in some places Stalinist) parties also dominated postwar governments in France, Italy, Czechoslovakia, Belgium, Norway and other European countries. The Social Democratic Party had been in power in Sweden since 1932, and Labour parties also held power in Australia and New Zealand. In Germany, on the other hand, the Social Democrats emerged from the war much weakened, and were defeated in Germany's first democratic elections in 1949. The united front between democrats and the Stalinist parties which had been established in the wartime resistance movements continued in the immediate postwar years. The democratic socialist parties of Eastern Europe, however, were destroyed when Stalin imposed so-called "Communist" regimes in these countries.

The Second International, which had been based in Amsterdam, ceased to operate during the war. It was refounded as the Socialist International at a congress in Frankfurt in 1951. Since Stalin had dissolved the Comintern in 1943, as part of a deal with the imperialist powers, this was now the only effective international socialist organisation. The Frankfurt Declaration took a stand against both capitalism and the Communism of Stalin:

Socialism aims to liberate the peoples from dependence on a minority which owns or controls the means of production. It aims to put economic power in the hands of the people as a whole, and to create a community in which free men work together as equals... Socialism has become a major force in world affairs. It has passed from propaganda into practice. In some countries the foundations of a Socialist society have already been laid. Here the evils of capitalism are disappearing... Since the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, Communism has split the International Labour Movement and has set back the realisation of socialism in many countries for decades. Communism falsely claims a share in the Socialist tradition. In fact it has distorted that tradition beyond recognition. It has built up a rigid theology which is incompatible with the critical spirit of Marxism... Wherever it has gained power it has destroyed freedom or the chance of gaining freedom...Anarcho-pacifism became influential in the Anti-nuclear movement and anti war movements of the time[125][126] as can be seen in the activism and writings of the English anarchist member of Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament Alex Comfort or the similar activism of the American catholic anarcho-pacifists Ammon Hennacy and Dorothy Day. Anarcho-pacifism became a "basis for a critique of militarism on both sides of the Cold War."[127] The resurgence of anarchist ideas during this period is well documented in Robert Graham's Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas, Volume Two: The Emergence of the New Anarchism (1939–1977).

— The Frankfurt Declaration, 1951

The first socialist government in a North American country